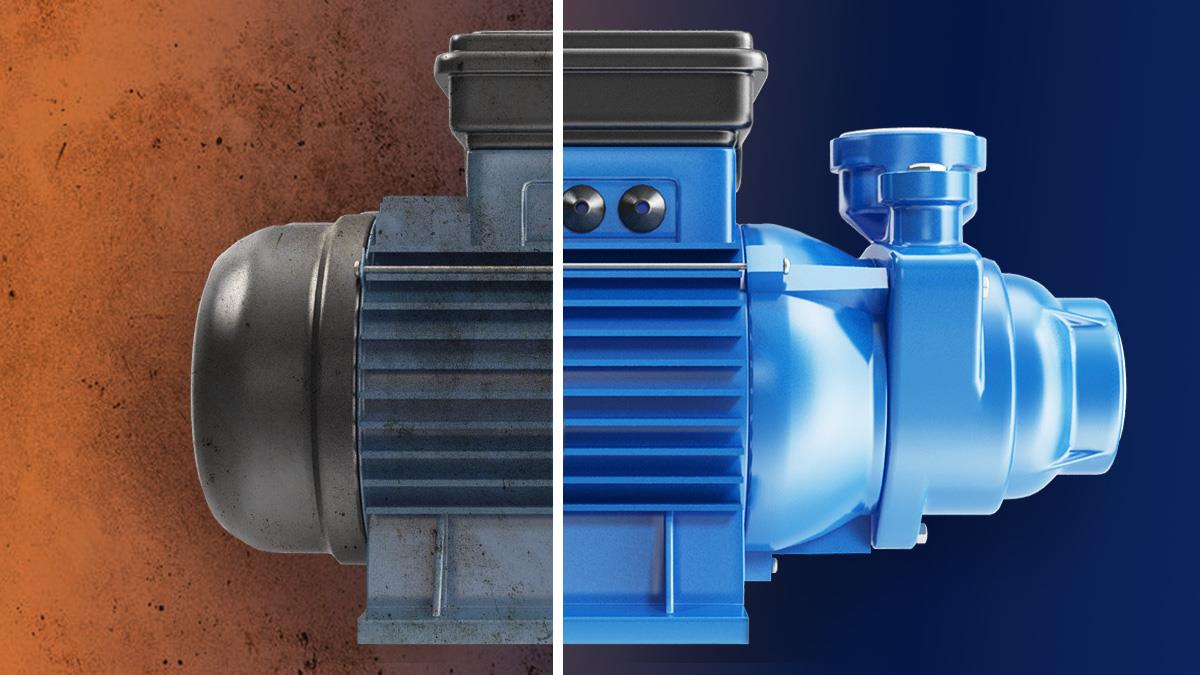

From Breakdown to Breakthrough: Rethinking Reliability in Centrifugal Pumps

For most engineers, the phrase “inherent reliability” is practically sacred: a machine leaves the factory with a baked-in limit to how reliable it can ever be. Maintenance and operating practices can help maintain that level, but they generally can’t raise it.

But what happens when a brand-new machine consistently fails long before its expected life? What if thirty newly installed centrifugal pumps — all API 610 VS6 vertical, multistage units — begin dropping out with mean times between failures (MTBF) as low as three months? That’s not disappointing; that’s catastrophic.

This case study follows what happened next. It’s a story of digging past assumptions, diagnosing the real culprits, and ultimately proving that when a machine’s original design is flawed or mismatched to its environment, redesign is not only possible — it’s the only way to restore the reliability the asset should have had from day one.

Instead of maintaining inherent reliability, the engineering team had to re-establish it.

The Situation: Thirty New Pumps, Thirteen Sites, One Big Problem

Across thirteen facilities, each operating a duty/standby pair of newly installed pumps, all units shared common specs:

- Type: Centrifugal, multistage, vertically suspended, double-casing, diffuser design

- Standard: API 610 VS6

- Service: Crude oil and produced water

- Stages: Three- and four-stage versions depending on the site

| # Stages | Speed | BEP | MCSF | Rated Flow |

Flow: Preferred Operating Region (70% to 120% of BEP) |

Flow: Allowable Operating Region (40% to 120% of BEP) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From | To | From | To | |||||

| 3 stages | 1488 rpm | 827.2 | 331.8 | 673.3 | 579 | 992.6 | 331.8 | 992.6 |

| 4 stages | 1488 rpm | 836 | 335.7 | 673.3 | 585.2 | 1003.2 | 335.7 | 1003.2 |

Almost immediately after commissioning, failures began showing up at a disturbing rate. Technicians found themselves pulling units after mere months — and in some cases even preemptively after only a few weeks — because degradation was so severe that major failures were imminent.

Early inspections painted the same picture across the fleet: critical rotor support components were wearing out far faster than any reasonable operating envelope should allow.

What Was Failing — and How Badly

As the teardown data accumulated, three components emerged as the biggest trouble spots.

1. Bushings

- These were the first parts to show abnormal degradation.

- Even pumps removed proactively after only one month showed excessive wear.

- The non-metallic, PEEK-based OEM design simply wasn’t surviving.

2. Sleeves

- Exhibited severe uneven wear, consistent across multiple sites.

3. Impellar & Case Wear Rings

- Damage severity increased with runtime.

- Even short-service pumps showed clear signs of premature wear.

Something wasn’t just slightly off — the failure modes pointed to systemic mechanical and hydraulic distress.

Root Cause Analysis: Two Smoking Guns

A comprehensive RCA revealed two primary mechanisms behind the short pump life. Both were serious. Together, they were devastating.

Root Cause #1: Operation Far Outside the BEP

The data showed every pump was operating dramatically below its Best Efficiency Point — between 26% and 49% of BEP, averaging only 36%.

API 610's preferred window? 70%–120% of BEP.

Running that far off-curve created excessive hydraulic loads, which directly translated into:

- Side loading

- Elevated vibration

- Increased radial forces on bushings and sleeves

No surprise those components were wearing unevenly — they were being punished every minute they ran.

Root Cause #2: Abrasive Solids in the Pumped Fluid

The second factor only made the first worse: the fluid contained unexpected levels of abrasive solids coming from the reservoir. This was not anticipated during design.

Abrasive particles acted like microscopic grinding media inside every critical interface:

- Bushing surfaces

- Sleeve outer diameters

- Wear ring clearances

Nothing in the OEM material selection or geometry was built to survive this environment.

Together, these two root causes made premature failure essentially guaranteed.

Exploring the Options: What Could Be Done?

When all failed units are brand-new, replacing parts in-kind is just repeating the problem.

The team evaluated multiple alternatives using a multi-factor decision framework that weighed:

- Technical feasibility

- Cost-effectiveness

- Probability of successfully mitigating the real root causes

The conclusion was unavoidable: the pumps required a redesign of key rotor components to survive both the hydraulic loading and the abrasive solids.

| Proposed Corrective Actions | Technically feasible? | Worth doing (cost-effective)? | Implementation is within our control? | Will not generate a collateral damage? | Fastest, simplest thing with the highest probability of success? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increase the pump flow recirculation rate | × | × | × | ✓ | × |

| Changing pump operational philosophy from 24/7 to on-demand | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × | × |

| Increase the pump flow to reach 70% to 120% of the BEP | × | × | ✓ | ✓ | × |

| Introduce VFDs (Variable Frequency Drivers) | ✓ | × | ✓ | ✓ | × |

| Redesign the pump (de-staging, impellers replacement, etc.) | ✓ | × | ✓ | ✓ | × |

| Modify suction strainer and DP protections design | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × | ✓ |

| Redesign the critical pump components (rotor supports) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

This wasn't "improving reliability through maintenance."

This was correcting a design mismatch so the pumps could achieve the reliability their process conditions demanded.

The Redesign: Building Components That Could Survive Reality

Three major component categories were redesigned or upgraded.

1. New Bushings

The OEM bushings had a single helical groove and were made of PEEK — inadequate for both load and abrasive environment.

The fix:

- Replaced single groove with six axial grooves for improved load absorption and solids handling

- Increased groove depth and width

- Upgraded material to a composite with carbon fibers in a silicon carbide matrix

These changes addressed both hydraulic loading and solids tolerance.

2. New Sleeve Bearings

The base material remained A276-410, but the team applied a specialized surface hardening process (TSC-NCB-2020-60) supplied by a U.S. vendor.

This proprietary blend of chrome, boron, tungsten carbides, and nickel created a sleeve capable of resisting extreme abrasion.

3. New Wear Rings

Casing wear rings:

- Upgraded to the same composite material used for the new bushings

Impeller wear rings:

-

Retained original A426-CPCA15 base

-

Added the same advanced surface hardening process used on the sleeves

These changes created a much more durable, solids-resistant rotor support system.

The Results: Reliability Restored — and Then Some

Two categories of upgraded components were installed and tracked:

Category I: Fully Upgraded Package

(bushings, sleeves, casing wear rings, impeller wear rings)

- New MTBF: ~5 years

- Improvement: 20× increase over original performance

- In some cases, the MTBF exceeded expectations entirely.

Category II: Partial Upgraded Package

(bushings + sleeves only)

- New MTBF: ~3 years

- Improvement: 12× increase

Comparison of Mean Time Between Failure (MTBF) of centrifugal pumps using various categories of spare parts: Original spare parts (a),

Upgraded spares Category I (b) and Upgraded spares Category II (c)

| Spare parts category | Mean Time Between Failure (MTBF) | Difference with original MTBF |

|---|---|---|

a) Original spare parts (reference)

|

90 days (3 months) | Not Apply |

b) Upgraded spare parts Category I

|

1825 days (5 years) | MTBF extended twenty times |

c) Upgraded spare parts Category II

|

1095 days (3 years) | MTBF extended twelve times |

Both solutions delivered massive leaps in availability, drastically reduced maintenance interventions, and lowered long-term operating costs.

What This Case Proves About Reliability

This experience reinforces a crucial but often misunderstood point:

Maintenance cannot increase a machine’s inherent reliability…

…but redesign absolutely can.

The pumps weren’t failing because they were poorly maintained.

They were failing because their original design assumptions were wrong:

- The hydraulic operating range was far outside what the rotors could tolerate

- The solids load was much higher than the OEM materials could handle

By upgrading materials, geometry, and surface treatments, the engineering team didn’t simply “improve reliability.” They corrected the design so the pumps could finally achieve the reliability their operating conditions required.

In other words, they restored — and in some ways established for the first time — the reliability these pumps should have had the day they were commissioned.

Brand-new equipment failing early is frustrating, expensive, and often politically charged. But it’s also an opportunity.

This case shows that when the operating environment doesn’t match design assumptions, no amount of preventive maintenance will save you. Reliability problems that come from design mismatches can only be solved through design intervention. By rethinking the internal architecture of key rotor components, the engineering team transformed a fleet of failure-prone pumps into long-life, high-availability assets — proving once again that reliability isn’t just something you maintain.

Sometimes, it’s something you have to rebuild.