Content covered:

- What is the definition of the speed factor in rolling bearings?

- What is the difference between speed factor and rotation?

- How to calculate the speed factor in rolling bearings?

- How does the speed factor work in lubricants?

- What are the impacts of the speed factor on lubrication?

- Practical example of the importance of calculating the speed factor.

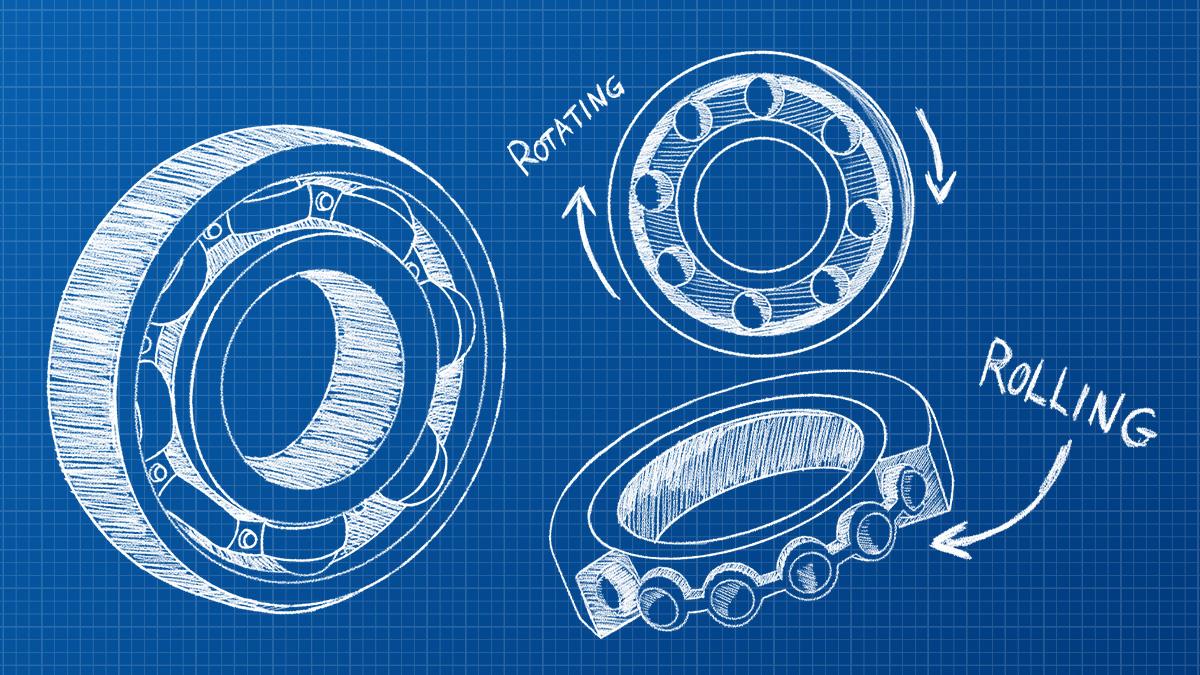

Speed factor, velocity factor, dn factor, NDm factor. Whatever you call it, this factor is extremely important when it comes to rolling bearing lubrication. It helps us understand the relationship between rotation and bearing diameter and how this affects the determination of the proper base oil viscosity, kappa factor calculations and the optimal amount of lubricant to apply.

What is the definition of the speed factor in rolling bearings?

Basically, the speed factor is a variable that expresses the relationship between a bearing’s rotational speed and its size.” This factor is typically expressed in units of linear velocity (i.e., displacement per unit time). Knowing this relationship is important, as considering only the rotation of the rolling bearing in isolation can mislead the selection of the ideal lubricant for the application. Using only the rotation to tell whether it is a low, medium or high-speed application can be shortsighted and miss crucial details.

What is the difference between speed factor and rotation?

Technically, the speed factor corresponds to a measure of linear (tangential) velocity, while rotation refers to angular velocity (angular displacement per unit time).

In practice the two are most commonly expressed as:

- Rotation (angular speed): rpm (revolutions per minute)

- Speed factor: mm/min (millimetres per minute).

Thus, in a simple unit of measurement analysis, the relationship between rotation and velocity (speed factor) can be defined and it depends on another dimension. To explain better, Figure 1 shows a rolling bearing with a certain rotation ω, rotating counterclockwise.

Figure 1 - Rolling bearing with rotation ω.

When selecting two points in this bearing, aligned with the center of rotation, in this case a red dot and a green dot (Figure 2), it is noticed that the red dot is farther from the center than the green dot. Both dots have the same rotation ω, however, can I say that they have the same linear velocity? That is, does the red dot move at the same speed as the green dot? The answer is no!

Figure 2 - Position of the red and green dots on the bearing.

By projecting two concentric circles that each pass through one of the two points, the red dot is positioned at a larger diameter than the green dot, correct? Therefore, the red dot has a larger perimeter to travel through than the green dot, however both dots take the same time to complete it. This means that the red dot travels at a higher linear speed, that is, faster than the green dot.

Equating this relationship, we have that the bearing has an angular velocity ω, which is the rotation, the green dot is in a radius range R1, so it will have a velocity V1, and the red dot is positioned in the radius range R2 and, therefore, will have a proportional velocity V2. Hence the equation relates angular velocity (rotation) to linear velocity through the diameter. The linear (tangential) velocity equals the angular velocity multiplied by the radius (which is equivalent to the diameter divided by two), as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 - Relationship between linear velocity and rotation.

And why is this important? Because what actually shears the lubricant is the linear velocity. The energy transferred to the lubricant is dependent on the velocity at which it is applied. It is the linear velocity that is directly related to viscosity, film formation and shear of the lubricant. In other words, finding out the speed at the point where the lubricant is actually doing its job is essential to determine the ideal lubricant.

This equation shows us that, for the same rotation, therefore, fixing the ω, the larger the diameter, the greater the linear velocity. In a more technical way: If two points travel concentric trajectories with the same angular velocity (rotation), then the outermost one must have greater tangential/linear velocity. This means that larger bearings will exhibit higher linear velocity than smaller bearings. And this will greatly impact the definition of the ideal lubricant for the bearing.

How do you calculate the speed factor in bearings?

After this explanation, one arrives at the calculation of the speed factor, NDm factor or velocity factor—whatever term you prefer. There is more than one way that is used to calculate this factor in rolling bearings. For our purposes, we will present the most common method that is based on the average diameter.

The speed factor is calculated as the rotation (in rpm) multiplied by the average diameter: (outer diameter + inner diameter) ÷ 2, as shown in Figure 4. This is because it is in the average diameter zone where the lubricant is placed to work.

Figure 4 – Equation for calculating the speed factor in bearings.

Any similarity of this formula with the linear velocity formula, seen in Figure 3, is not a mere coincidence. This is pretty much the same equation. The only caveat is the units, which here do not consider conversion of units from revolutions per minute to radians per second, and that the diameter is preferred rather than the radius. In this equation the common everyday units (rpm for speed and millimetres for diameter) are used. The results of this calculation with these units are already world-known references published in literature and used in the industry.

Therefore, it is the result of the speed factor calculation that will be considered to say whether it is a high, medium or low speed application, and not the rotation in isolation.

How does the speed factor work in lubricants?

Typically, grease technical data sheets specify the maximum speed factor that the lubricant supports. This suggested maximum value is a way of indicating how well the grease can flow, generate lubricating film and fill spaces on the bearing. Type and viscosity of the base oil, thickener type, and additives are all variables that play an important role in defining the speed factor of the lubricating grease. In general, lubricant manufacturers refer to industry literature (based on base‑oil viscosity and thickener type) to determine the speed‑factor limit shown in the data sheet. It can also be done by rheometric analysis to help identify the capacity of the grease in supporting different ranges of velocity and how its dynamic viscosity varies.

Viscosity, in short, is a fluid’s resistance to flow and shear. The higher the viscosity of the oil, the greater its resistance to these forces. When a high‑viscosity lubricant is used between two surfaces at high tangential speed (i.e., under high shear), it generates proportionally higher resistance, which reduces efficiency and increases operational temperatures. Therefore, the higher the base‑oil viscosity, the lower the supported speed‑factor will be.

The type of thickener and the additives also play an important role in this characteristic of supporting the velocity and shear. Some thickeners are "heavier" because they are added in a higher concentration to the grease formulation. For example, a calcium sulfonate complex grease can have around 30% of thickener to achieve NLGI 2 consistency, while a lithium complex grease only needs around 12%.

Some additives add a more fibrous characteristic to the grease. These additives are typically added to improve adhesion and prevent drips, and one can basically divide it in two forms: long fibers (with the additive) and short fibers (without the additive). In short, greases with short fiber have a smoother texture, are more pumpable, and allow for a higher speed factor. Greases with long fiber, on the other hand, offer greater resistance to flow and have poorer pumpability, which converts into a lower supported speed factor.

A very simple way to see the difference between short and long fibers in grease is to place a small sample of grease between your index finger and thumb and press them down and separate them. Short-fiber grease breaks with little elongation, while long-fiber grease tends to stretch more into a single fiber bundle, as shown in Figure 5. In any case, it is a trivial method and factors such as base oil viscosity and thickener type can make it difficult to interpret.

Figure 5 - Comparison of long and short fiber greases.

To show some examples of greases datasheets, in Figures 6 and 7 we have, respectively, Interplex, with 1000 cSt of base oil, calcium sulfonate complex thickener and speed factor of 150,000, and Sintaplex, with a base oil of 32 cSt, lithium complex thickener and has a speed factor of 1 million.

Figure 6 - Interplex technical datasheet.

Figure 7 - Sintaplex technical datasheet.

Example of calculation: A rolling bearing 22338, outer diameter of 400 mm, bore diameter of 190 mm and rotational speed of 1800 rpm. Using the formula presented in Figure 4, it could be calculated a speed factor of 531,000 mm/min, i.e. high-speed application. Which of the greases shown above would you select? The answer is: Sintaplex. The reason for this choice is that Sintaplex supports up to 1,000,000 speed factor. Interplex supports only 150,000. If we were to place Interplex in a bearing with a 531,000 of speed factor, we would certainly observe an increase in bearing temperature and possible grease centrifugation.

What are the impacts of the speed factor on lubrication?

We have seen that calculating the bearing speed factor is extremely important for determining the ideal base oil viscosity. However, in addition, the speed factor impacts other factors that are decisive for world-class lubrication, including: kappa factor, optimal amount of grease applied and relubrication interval.

The kappa factor is a way of determining the optimal viscosity of the base oil based on the rotating speed. In general, according to ISO281:2007, the kappa factor is the division between the viscosity of the oil at the operating temperature and the reference viscosity defined according to the dimensions of the bearing and its rotation (i.e., its speed factor). The well-selected kappa factor, i.e., with values between 1 and 4, suggests that a lubricating film of ideal thickness will be formed between the parts in contact, that is, neither too thick to increase fluid friction and temperature and not too thin to allow metal-to-metal contact.

The speed factor is also highly important in determining the grease fill volume. In general, the higher the speed factor, the smaller the volume of grease that should be applied.

To explain this with an analogy, we can use the example of a car being driven on a road with the window open. The fluid (in this case air), generates a certain resistance to the vehicle and with the window open, this resistance is even greater. As the speed of the vehicle increases, the resistance imparted by the air also increases. At a certain speed, the air resistance is so high that it makes sense to close the windows and turn on the air conditioning because even after doing so, you will see lower overall energy consumption (in this case, fuel). In this analogy it is apparent that velocity is directly related to the resistance generated by the fluid.

Another analogy that can be used to explain this effect is when we are in a pool and try to move around. The deeper we are submerged into the water, the more difficult it will be to move around and the more energy we will expend. And the faster we try to move, the greater the water’s resistance to our movement.

Following this line of thought, the faster a bearing runs, the greater the resistance that the lubricant (in this case, grease) will present to the motion. Therefore, an excessive amount of grease in a high-speed bearing can generate extreme resistance to movement, increasing energy consumption and operating temperature.

It is common to see general recommendations to fill 1/3 of the free space of the bearing from companies like SKF and FAG. This is indeed a good approximation, but only for bearings at medium speeds. Generally, the optimal amount of grease should be determined by data like the speed factor range, as shown in Figure 8. Rolling bearings in low speed can be packed with grease because the churning losses will be almost negligible. Rolling bearings in high speed must be filled with a lower quantity, suggested here as 10 to 15% of the free space of the bearing.

Figure 8 - Speed factor and suggested amount of grease.

Obviously, the speed factor is only one of the factors that influence the determination of the ideal amount of grease. Contamination conditions, for example, can also impact this amount and, therefore, we must consider all the operational and environmental conditions of the application to define the optimal volume.

Finally, the speed factor also impacts the life of the grease in operation, that is, the lubrication interval for the bearing. Most bearings in critical applications must be relubricated and, as much as new condition-based lubrication techniques are emerging and can demonstrate high efficiency, there are still many cases where lubrication is done preventively (based on time).

As already mentioned, the grease in the bearing is repeatedly sheared and degrades over time. The faster the bearing rotates, the more working cycles the grease must withstand and the greater the shear stress presented. Thus, the higher the speed, the faster the grease will lose consistency, lose oil and lose other essential properties. The sum of these losses represents the degradation of the grease and of the bearing lubrication. In high-speed applications it’s inevitable that we will have to replace the grease in shorter intervals than in slow speed applications.

Again, numerous other factors will impact the grease lubrication interval, not just the speed factor. Therefore, considering all the conditions in which the bearing is subjected is the most correct way to achieve world-class lubrication.

Practical example of the importance of calculating the speed factor.

Consider two bearings of different diameters, but both with the same rotation, exemplified here as 400 rpm. As explained earlier, it is known that the linear speed of each one will be different at the point where the lubricant will be placed. In other words, the linear velocity at the point of average diameter will be greater in the bearing with the larger diameter.

In this example, the smaller bearing has an average diameter of 90 mm, while the larger bearing has an average diameter of 550 mm. The result of the speed factor calculation will be 36,000 and 220,000 mm/min for the smaller bearing and the larger bearing, respectively, as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9 - Practical example calculations.

Therefore, there are bearings with the same rotation that work the lubricant with different speeds and might need to use different lubricants, applied at different quantities and at different lubrication intervals to achieve optimal lubrication.

Giving an example related to the applied amounts of grease, using the references in the table in Figure 9, the largest bearing (ndm = 220,000 mm/min) is in a medium speed range, filling 30 to 40% of the bearing's empty space. The smaller bearing (ndm = 36,000 mm/min) is in a very low speed range, with a recommended filling of 70 to 100% of the bearing's empty space.

Therefore, when selecting bearing lubricants and specifying fill volume, one should not rely on rpm alone. For instance, 400 rpm alone does not indicate the lubrication regime if the bearing size is unknown.

The weak point of this theory is that it does not consider a very important factor: the temperature. So, the next step will be to consider this variable through the kappa factor theory.

Conclusion

In summary, the speed factor is the key link between a bearing’s rotation, its diameter, and the behavior of the lubricant. It determines the linear velocity at the point where the grease works, guides the selection of base-oil viscosity, and dictates the optimal grease volume and relubrication interval. Bearings of different sizes but identical rotations experience very different linear speeds, making the speed factor essential for precise lubrication planning. Ignoring it in favor of rotation alone risks improper lubricant choice, excessive shear, higher temperatures, and reduced bearing life. Accurately calculating and applying the speed factor ensures that lubrication is tailored to the actual working conditions, achieving efficiency, reliability, and longevity.